Gerda Rosenthal

About Gerda Rosenthal

Gerda Rosenthal was born in Remscheid in 1917 as the second child of Polish immigrants. Her father owned a shoe shop there. In the mid-1930s, she was the only one in the family to manage to emigrate to Jerusalem with the help of the organisation 'Kinder- und Jugend-Alijah', where she stayed in a home run by the organisation. She later worked as a nanny in Israel. At the end of the 1930s, she returned to Germany on a one-year visa to visit her parents. They were later murdered by the National Socialists. However, her brother, who was four years older, survived the war and later also emigrated to Israel. It was in Jerusalem that Gerda Rosenthal met her husband, with whom she had two children. Her son died at a young age. Her daughter now lives in America, where the family later emigrated to. Gerda Rosenthal lived in the Henry and Emma Budge Foundation in Frankfurt am Main until her death.

Gerda Rosenthal died in November 2019 at the age of 102.

A picture to live on

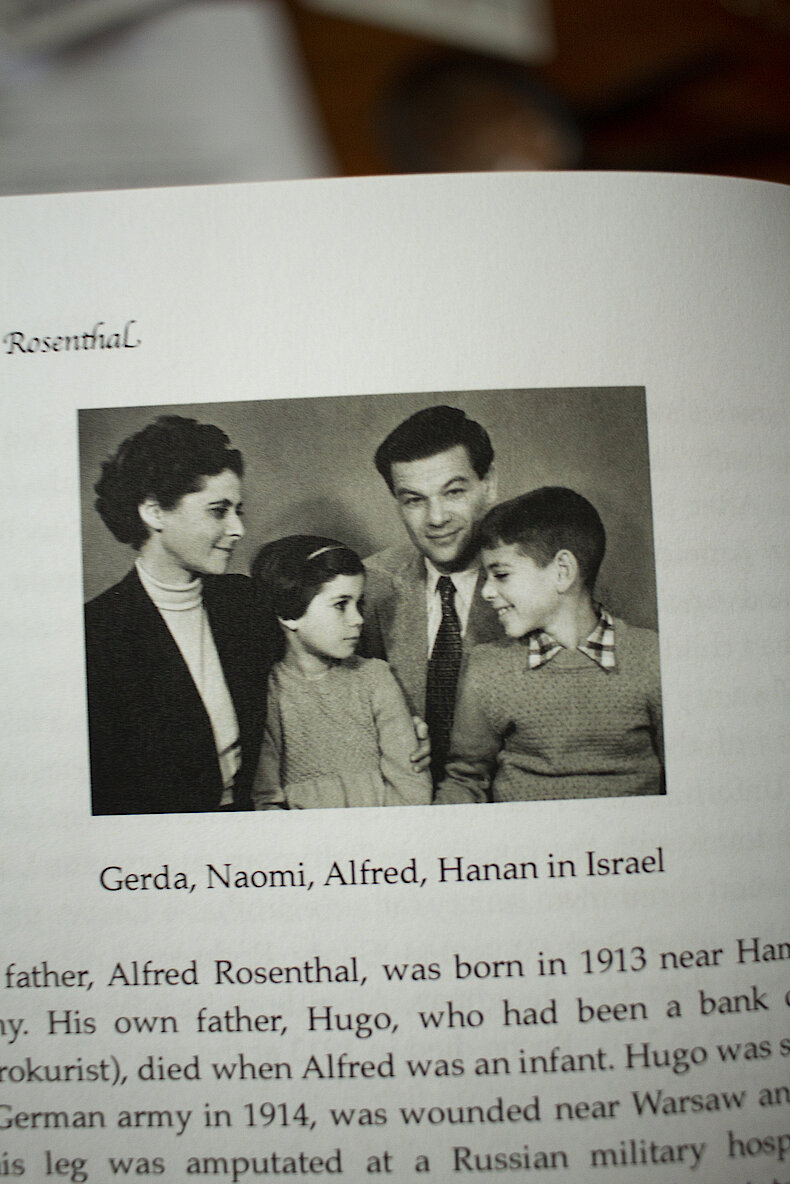

Gerda was particularly proud to show us a picture of her family, which appeared in her daughter's book. Gerda talked a lot about her husband and children during our meeting and you could tell that her family is very important to her. Especially in the time after the war, they gave her a lot of strength so that she could start a new life.

Our encounter

Gerda Rosenthal had a small flat in the Budge Foundation, a Jewish-Christian retirement home in Frankfurt. The moment we entered her flat, we almost forgot that we were in a retirement home. Inside, it looked like grandma's home: Persian carpets, lace doilies and lots and lots of picture frames. Right from the start, I was amazed at how much I could identify with young Gerda. How she hitchhiked to Elberfeld with her cousin to enjoy the excitement of city life. How she emigrated to Palestine alone at the age of just 17, the same age I was when I first went abroad for a longer period of time. Precisely because I could identify so well with Gerda Rosenthal myself, I was all the more affected by how advanced her dementia had become. After only a short time, we began to go round in circles in our stories – a never-ending loop from which there was no escape. By the end of the interview, I was trapped in a labyrinth of stories that didn't quite fit together and probably never would again. But even if we have now lost the whole picture, the mosaic still told its very own story. And this story is also worth hearing, remembering and passing on.