Chava Wolf

About Chava Wolf

Chava Wolf was born on 7 July 1932 in Bukovina, which was then part of Romania and is now part of Ukraine. She wanted to study medicine, but this was not possible: in 1941 she was denied access to school because she was Jewish, and the family eventually had to leave the city and lived in various camps and ghettos in Transnistria (formerly Romania, now Moldova) until 1944. This time shaped Chava for the rest of her life. After liberation, the family returned to Bukovina in 1945, but Chava did not want to stay there. Her first attempt to reach Israel failed. She left the internment camp on Cyprus, where she had to live for three months, during a night-time escape and made it to Israel after all. Chava's parents did not follow her until 18 years later - by this time she had married and become a mother. For decades, she did not talk about her painful experiences, instead Chava processed them in pictures and poems. She died in Tel Aviv in February 2021.

"I want to tell what we went through so that we don't have to relive what happened."

A picture to live on

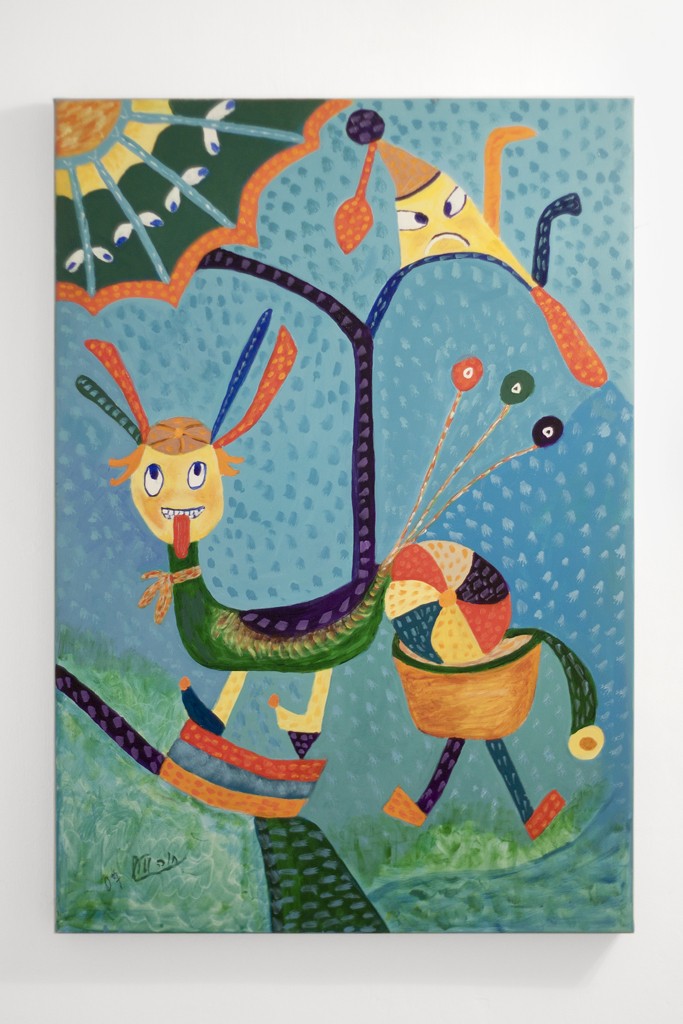

Expelled from Bukovina, Chava experienced things in the camps of Transnistria that she was unable to talk about for 60 years. Art and poetry gave Chava the opportunity to come to terms with her trauma. It was a kind of self-therapy for her. When she told us the stories behind the colourful and naive pictures, we immediately felt how present her past still was in her present. Chava told us: "In the songs and poems I write the real pain and in the pictures I draw the pain, but also with colours and optimism."

Our encounter

In Chava's small flat on the second floor, we admired her works as a painter in many rooms. But the naively colourful pictures took on a completely different, darker meaning for us in the context of her story. The colours and poems help the survivor to express what she has experienced. Chava told us that all the conversations with psychologists had not helped her process her past as much as her art and poetry.

In our search for a suitable setting for the portrait, her bedroom caught our eye. All the walls were covered with pictures of her family, and in the corner stood the porcelain doll with which she bought back a piece of her childhood at the age of 70. It seemed as if Chava kept everything of personal value here like a treasure. In the midst of these witnesses to her new life, we photographed her in a way that shrouds her in light shadows - fears that accompany her.

Above all, Chava wanted to be heard. Her poems and pictures are calls for people to recognise her. It is shocking that someone who has lost years of her life and the carefree life of her youth has received no support and had to live in such humble circumstances.

We met her husband briefly at the door. Almost pleadingly, she bid us farewell with the words: "This is my husband. He was also in a concentration camp. Never forget our story."

We won't either. We couldn't do it.